For years, flying to Hawaii meant boarding a big airplane. Two aisles and a cabin that felt built for trans-Pacific distance. Hawaiian Airlines didn’t just operate widebodies; it was defined by them. The brand, the route maps, and even the psychology of trips revolved around that idea. For many years, Hawaii wasn’t treated like another long domestic sector. It was treated like somewhere far.

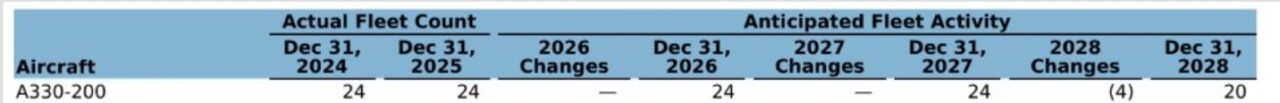

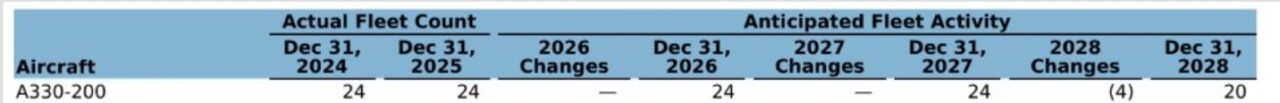

Other U.S. carriers fly widebodies to Hawaii, but almost exclusively on longer East Coast and hub routes. Alaska, American, Delta and United rely on narrowbodies for West Coast-Hawaii flying. The last carrier that built its entire long-haul identity around widebody service to and from the islands was Hawaiian Airlines, with a fleet of 24 Airbus A330s and earlier plans to grow further with Boeing 787 Dreamliners.

That all changed when financial losses forced Hawaiian into a sale to Alaska Airlines, a carrier that had only ever served Hawaii with 737s. Under Alaska, Hawaiian’s losses have been cut roughly in half, but reducing losses is not the same as turning a profit. The fleet plan now being filed with regulators starts to reflect that pressure.

We pulled the Hawaiian (Alaska) 10-K filing from February 12 and went straight to the Hawaiian fleet schedule showing exactly how many aircraft the company plans to operate, acquire, and retire in the years ahead. When you look forward two years to 2028, the widebody picture starts changing.

The A330 fleet gets smaller, even as it gets nicer.

Today, the fleet has 24 Airbus A330-200 aircraft. Those aircraft remain the backbone of the airline’s long-haul Hawaii flying. They handle many mainland routes that still feel like the traditional Hawaii experience, and they support the international services tied to Honolulu around the Asia Pacific region. Through the end of 2027, that aircraft count stays flat at twenty-four.

In 2028, four A330 widebodies are scheduled to leave the fleet, bringing the total down to twenty. That is not an isolated move. That same year, four Boeing 787-10 Dreamliners arrive at Alaska, and the MAX 10 fleet, which begins arriving in 2027, continues to grow. The timing is deliberate and reflects a reshaping of the fleet around different aircraft.

The arriving 787-10s are tied to Alaska’s global expansion out of Seattle, not to replacing lost A330 capacity in Honolulu. As we reported last July, the Honolulu Dreamliner base has been described internally as supporting roughly five aircraft. That means Hawaii’s A330 reduction does not automatically come with equivalent widebody growth at home.

Alaska’s $600 million Kahuʻewai Hawaii Investment Plan focuses on airport infrastructure and guest facilities. Separately, the company has announced a full A330 cabin rebuild beginning the same year, in 2028. That is a meaningful investment in the aircraft themselves, even if it will be on a smaller fleet. Whether Alaska plans to reduce the A330 fleet beyond what we currently know is not disclosed.

The airline’s MAX 10 fleet will ramp up aggressively across 2027 and 2028. When those aircraft enter the system in large numbers, the economics of mainland-Hawaii flying change. A higher-capacity narrowbody with more premium seats makes it easier to justify flying a MAX 10 on some Hawaii routes that historically might have supported an A330.

If Hawaii loses A330 aircraft and does not gain an equal number of Hawaii-based Dreamliners, then fewer large aircraft will depart from and arrive in the islands. Fewer large aircraft also means less cargo space tied to Hawaii. Cargo is a layer that does not appear on passenger seat maps. The A330 carries significant belly freight, which matters in geographically remote Hawaii for fresh food, mail, medical supplies, and international freight connections. Narrowbodies cannot replicate that space, so when widebody counts shrink, cargo lift tightens unless frequency increases.

Widebodies aren’t going away. But with fewer of them, there’s less flexibility. Every new route or schedule change has to come from somewhere else.

The Dreamliner growth is centered elsewhere.

The Dreamliner side of the filing reinforces what we reported last July. An internal memo shared with Beat of Hawaii and later confirmed by multiple aviation sources described Honolulu’s 787 base as capable of supporting five aircraft.

The current filing gives that more context. Alaska operates five 787-9 aircraft today and will add one in 2026 and another in 2027. The larger 787-10 variant begins arriving in 2028, with four deliveries scheduled that year. By the end of 2028, the fleet will consist of seven 787-9s and four 787-10s, with additional 787-10 aircraft on order beyond that.

If Honolulu remains limited to five Dreamliners while the fleet grows, the majority of those aircraft are clearly based somewhere else, just as the new Dreamliner branding tells the same story. Every 787 now wears Alaska’s global livery, and the long-haul expansion messaging consistently centers on Seattle.

There is another constraint. With only five Dreamliners in service today and one more arriving next year, Alaska is already rotating those aircraft across Seattle-NRT, ICN, LHR, and FCO. Even the Seattle–Tokyo (NRT) route returns to the A330 on April 22 because there simply are not enough 787 aircraft to cover everything. That reality makes clear that dedicated Dreamliner growth out of Honolulu, beyond the limited base previously reported, is not in the near-term picture.

The MAX 10 changes the mainland-Hawaii equation.

The biggest fleet growth in the entire reveal document is not on the widebody side. Alaska will take delivery of fifty 737 MAX 10 aircraft in 2027 and 2028, a huge number in just two years. On its earnings call, Alaska said the MAX 10 will add 5.5 percent more seats and 25 percent more first-class seats compared to the MAX 9.

A higher-capacity narrowbody with more premium seats makes justifying flying a MAX 10 easier on some Hawaii routes that historically might have supported an A330. That does not mean widebodies vanish overnight from Seattle-Honolulu or Los Angeles-Honolulu, but it does mean the economics no longer automatically favor deploying a 278-seat widebody aircraft.

Hawaii remains important, although it is no longer the growth center.

Nothing in the filing suggests Alaska is abandoning or downsizing Hawaii overall. Twenty refreshed A330s would still represent a very large widebody presence. The Hawaiian A321neo fleet remains intact through at least 2028, based on the 10-K, and the Hawaiian 717 interisland fleet shows no immediate replacement even as those planes move deeper into the final period of their lifespan. Both of those fleets, however, remain vulnerable to change.

Hawaiian Airlines was built as a widebody airline that served Seattle. Alaska is building a Seattle-based global airline that serves Hawaii. That distinction becomes obvious when you look at where the new aircraft are going and where the older ones are leaving.

The widebody era in Hawaii is not ending, but it is becoming more defined and less expansive than ever before. The 10-K simply lays out the fleet, year by year, through 2028.

Have you noticed a difference in the aircraft on your Hawaii flights recently?

Primary source: Alaska Air Group Form 10-K filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on February 12, 2026 (Accession No. 0000766421-26-000010).

Get Breaking Hawaii Travel News

As long as there are enough seats and prices can stay reasonable, most travelers won’t care what aircraft it is or whether it has one aisle or two.

One real question is whether MAX 10 economics makes it easier to drop widebodies from certain routes over time.

The A330 had felt like part of the Hawaii experience since they first got here. It’s been more than just transportation, but the start of the trip experience itself.

I just don’t understand the fixation on HA’s A330s. They are old and tired and show it. We flew the A321NEO last week LIH – LAX and thought it was much better than the A330. We’ll be flying AKL – HNL in a few weeks on a HA A330 overnight in business class. Hopefully the planes HA flies on international routes are in better shape than what the ones that fly to LAX are.

Narrowbodies are clearly cheaper to operate. Airlines just follow the economics, not sentiment.

The 717 situation worries me more. Those planes are old and I don’t see a replacement plan anywhere in sight. Why?

If they start flying MAX 10s to Hawaii instead of A330s, that’s a significant downgrade for passengers. Period.

Seattle is the corporate base. Of course that’s where growth goes. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. But I don’t understand why Honolulu would be capped at five Dreamliners. That seems like an odd ceiling. Won’t the Dreamliners eventually replace the 330?

I’ve been saying this since the start. Alaska didn’t buy Hawaiian to grow Hawaii. They bought it to grow Seattle.

Good work, gentlemen.

Just hoping that Hawaiian continues to provide options to arrive comfortably.