We arrived at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park between eruptions 39 and 40. That timing detail sounds fine on paper, although certainly not what we had hoped for. But it felt entirely different once we were there, in many ways. We missed the 9-hour eruption that preceded us by just a few days, and that fact hung over the entire visit. The volcano was temporarily quiet, but it was anything but calm. Steam vents were very active. A red glow was visible at night. You could feel, in a way that is hard to explain until you experience it yourself, that the ground beneath you was very much alive.

That sense that we were sandwiched between eruptions is the reality visitors often face right now. You are not guaranteed lava fountains or dramatic flows, but you are also not visiting a dormant park. This is a living system, shifting day by day, sometimes hour by hour. Even without active lava, the park felt charged. There was heat and steam in places you did not expect, sulfur in the air, and a quiet intensity that made it clear this was not a static museum or merely a landscape.

Steam, glow, and the feeling that something is happening.

Steam vents were active and impossible to ignore. At Wahinekapu, also known as Steaming Bluff, the sensory experience is immediate. You can see the steam rising, hear it escaping, and smell the unmistakable sulfur carried on the wind. It is not subtle, and it does not let you forget where you are standing. This is not just scenery, but rather geology in motion.

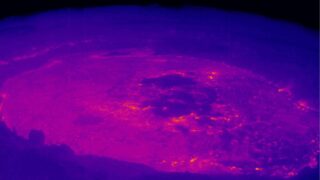

At night, the glow was visible from multiple points around the park. It was not dramatic in a postcard way, but it was unmistakable nonetheless. Even without lava fountains, the horizon had a faint, otherworldly light that reminded you that magma was not far below the surface. Standing there after dark, bundled up against the cold at the 4,000 ft. elevation, the feeling was less about spectacle and more about scale. This is Earth doing its thing, and you feel like a temporary guest. Everyone there is.

That timing tension is part of the experience right now. Visitors are watching USGS updates, hoping for eruptions, adjusting plans, and sometimes missing events by hours or days. That was us. We were on the wrong side of the line, not by far, just a couple of days, but the park still delivered something very powerful. The volcano did not need to perform to make its dramatic presence known.

Crowding is the real issue visitors need to plan for.

What surprised us most was not the quiet moments, but the crowding shown in our lead photo taken on Crater Rim Drive. This was not during an active eruption, and yet congestion was intense in multiple key areas. The road at the top of the park backed up for long distances, especially near Thurston Lava Tube. Traffic stopped dead. Parking was scarce. People spilled out onto road shoulders and walkways in uncomfortable ways, and, at times, it was genuinely unsafe.

This was not some weekend anomaly. Staff told us plainly that when an eruption happens, everything backs dramatically, all at once. Roads clog. Parking disappears. Entrance to the park is impossible. People abandon cars wherever they can. The word “chaos” came up more than once, and it was clear they were not exaggerating. If this is what a non-eruption day looked like, eruption days clearly push the park far beyond its limits.

Volcano House, which sits at the center of the park’s activity, becomes part of this congestion whether you are staying there or not. It functions as the main gathering point for day visitors, with restaurants, views, gift shops, and bathrooms all in one place. That means constant foot traffic, full and far too small parking lots, and a steady churn of people coming and going throughout the day, from morning to night.

There is no dedicated parking for lodge guests. When the nearby lots fill, you are left circling or walking. One night, we ended up parking roughly a mile away and walking back in the dark. That walk turned into a great hike we would not have discovered otherwise, but it was unplanned and inconvenient. Parking here in the park is not a small detail. It shapes the entire experience.

Kilauea Military Camp, beyond Volcano House, is also open to all park visitors for food and beverage services. That includes their cafeteria-style breakfast and dinner. Overnight guests are limited to active-duty and retired military personnel.

Timing is the only real workaround.

Cars start arriving early, but the volume noticeably ramps up around 9 am. Before that, the park feels completely different. Early mornings are pristine. Parking is manageable. Trails are accessible. The sense of space returns. If you can start your day early enough, you will have a fundamentally better experience.

The same is true after dark. Once the day visitors leave, the park settles again. The noise drops. The glow becomes more apparent. Walking around at night feels calm and enjoyable rather than chaotic. There are no tour buses. This is where staying inside the park, or very close to it, becomes a strategic advantage.

This is not about luxury or convenience. It is about being able to bookend the severe crowding. If you are only visiting during the middle of the day, you are seeing the park at its most stressed. Early and late hours show you something completely different and magical.

Crater Rim Drive is the “postcard” zone.

It’s where most visitors spend the bulk of their time, and it is easy to see why. This is the stretch that delivers the classic first impressions: broad caldera views, overlooks into Halemaumau Crater and Kaluapele (Kilauea Caldera), short walks that feel accessible even to casual visitors, and pullouts that let people absorb the scale without committing to long hikes.

It is also where the park’s intensity is most compressed. Traffic slows as cars leapfrog from viewpoint to viewpoint, parking fills quickly at Nahuku (Thurston Lava Tube), and pedestrians spill across narrow road shoulders. The scenery here is undeniable and often stunning, but this is also where the park feels smallest, busiest, and most fragile.

For many visitors, Crater Rim Drive is the park, so timing and expectations are especially important if you want those views without the stress of peak congestion.

Chain of Craters Road is where the park opens up.

When the summit area became too crowded, we drove Chain of Craters Road down to the ocean. It was late morning, a time when the top of the park was packed to the brim, and yet we had much of the road to ourselves. The drive takes under an hour each way, descending roughly 3,700 feet over 19 miles from the summit to the coast below.

This road used to be the main attraction when lava regularly flowed to the ocean. Since activity shifted back to the summit, it has been somewhat overlooked. That is a mistake. The drive is dramatic, varied, and expansive. It gives you room to breathe, both literally and figuratively.

The scale of the park becomes apparent quickly. Vast lava fields stretch out in all directions. The feeling of being hemmed in by crowds of visitors disappears. The road itself becomes part of the experience, a reminder of how large this UNESCO park really is.

There are no services along the way. No food, no water, no fuel. You need to come prepared. The stops we made along the route included Kealakomo Overlook, which offered panoramic views of the ocean and the vast lava field that covered its ancient village. Once at the ocean, we explored the area around Holei Sea Arch. We found this one of the most enjoyable ways to escape congestion and see the park beyond its busiest choke points.

Hawaii’s only UNESCO site you can actually visit.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. Hawaii has only two such sites, and the other, Papahānaumokūākea, is not open to the public. This is the only one you can actually experience in person.

The park spans more than 330,000 acres and contains two of the world’s largest volcanoes, Mauna Loa and Kilauea. That scale is difficult to grasp until you spend time moving through it. The park feels bigger than life, not in any marketing sense, but in a physical, humbling way.

Culturally, this is also a deeply significant place. Kilauea is home to Pele, and traditional practices, offerings, and protocols continue here as they have for generations. This is not just a natural site. It is a living cultural landscape layered with meaning that goes far beyond tourism.

Practical realities worth knowing before you go.

The park entrance fee is $30 per vehicle and is valid for seven days. There can be a backlog to enter the park, depending on the time and day. The visitor center is still closed for renovation, with information services relocated to Kilauea Military Camp. That catches some visitors off guard and is worth knowing in advance.

Dress in layers. The summit is chilly, especially after dark, and conditions change quickly. If you drive down the Chain of Craters Road, you’ll go from cold to warm at sea level. Bring a flashlight if you plan to be out at night, and use your phone’s low-light camera settings to capture the glow. Vog can be an issue for those with respiratory sensitivities, and those conditions shift rapidly. Checking USGS and National Park Service alerts before visiting is not optional if you want to avoid surprises.

We suggest staying inside the park or at nearby Volcano Village to be first in line for the Crater Rim Drive and parking areas. Then save the longer drive on Chain of Craters Road for later.

What comes next?

We spent three days inside the park. That experience shaped how we moved through the crowds, how we timed our days, and what we saw when others had already left. Our full review of that stay at Volcano House is coming next, because where you sleep here matters almost as much as when you arrive.

We’d love to hear about your experiences at Volcanoes National Park.

All Photo Credits – Beat of Hawaii at Hawaii Volcanoes. Our lead photo shows traffic delays on Crater Rim Drive.

Get Breaking Hawaii Travel News

dont know but why dont they just ban cars anywhere on and near the parks altogether, restricted, limited visits by appointments and bus service only. can they do that?

No. It’s simply not practical.

I live nearby. The traffic has been like “L.A.” with each of the 40 separate eruptions since Christmas, 2024. Local’s “secret”: there are four (4) legal (maintained road or trail) “side entrances” to the Park, all are off of the main highway, and all on the Left side of the highway as one drives away from the Hilo direction and towards the South Point direction. Watch closely to see them; are all very visible, & best on a BICYCLE, or E-Bike. One side entrance is toward Hilo from the Park Entrance & you can bike all the way to the Devastation Trail viewpoint area; three side-entrances are past the Park entrance & lead to various viewpoints along Crater Rim Drive. No lines, no traffic, no cost, & no ID’s needed. Park directly across the highway from all 4. Flashlights essential! Paved trails allow bikes; best to walk your bikes on gravel trails for others’ safety. Be prepared for cold + possible rain (no shorts).

We were lucky to be in the park for event 40 around noon. Very busy, but rangers did a great job. I was surprised and disappointed that they were not collecting the entry fee. We have been coming off and on for 48 years. Beautiful cloud above the fountain that day.

They suspend collection of entry fees during an eruption, especially when traffic starts to back up on Highway 11. I live on Volcano Golf Course & it has taken me over 2 hours to get home from mile marker 25 (transfer station).

More and more, the natural and cultural ‘āina ( and ocean ) events are seemingly excluding kanāka ma’oli and locals simply because they are so crowded. Not that anyone sets out to exclude them but no one living there has the kind of time to join the wait/crawl on the roads and waiting in the parking lots. What about using capacity restrictions? What about giving precedent to Hawaiians in this wahi pana, and locals over tourists during certain times at the park or all of the time ? ( again a limit on entering). Ditto the beaches and camp sites. People who live on the ‘āina need to come first. Not tourists/tourism. There are many places “ lost” to locals use because too crowded or there is not enough parking ( Ko Olina). It is not pono. It breeds contempt.

Fortunately or unfortunately, depending upon your perspective, this is a national park. The U.S. government cannot provide benefits to groups without Congress approval. And somehow, I suspect most legislators don’t care about residents of Hawaii.

I haven’t been to the Big Island in 30 years, but want to go back now that I live on Maui. However, I think I will be disappointed because it was so different back then. The 1st time I went, they let people walk over the rocks with the fire underneath ….I now wonder what type of shoes we had on because they should have melted! The 2nd time, I wanted to see the flames at night time (as shown on postcards!) so we drove through the park in the dark and it was so foggy that we decided to turn around (which of course, was scary because you didn’t see where you were going). Luckily, at that time, we didn’t have to deal with any other tourists. We were the only ones on the road at that time! Amazing how things have changed ….

Eva, don’t give up. Check USGS “Kilauea–Volcano Updates, U.S. Geological Survey” often. They are very accurate in predicting, within 48-72 hours, the next eruption. Meanwhile, look at flights to Hilo (closer than Kona); have your bag packed, rental car & room reserved & be ready to go. That’s my “local’s advice” if you want to see an upcoming eruption, because they only last, on average: 6-12 hours, & then the high fountaining show is over.

Mahalo for the info. Will check this out!

The Vog is very real and if you have allergies or any respiratory issues it’s not a good place to be.

We’ve been there twice and it was like this both times. Once, long ago, is when the lava was flowing outside the park and taking out homes. This last time was in August 2023, with no sign of activity in sight. It was still crazy everywhere we went. The caves were probably the worst of any place in the park. There was a line on the shoulder of the road, with people queued up waiting for a spot. The wait was long, but at least people were polite.

Busy but park rangers do an excellent job of controlling traffic at the park. Mahalo to them!